A few months ago, I was approached by the folks at eze System, who wanted to know if their ezeio product would work with AyrMesh to help farmers measure conditions on farms and control equipment.

They were kind enough to send me one of the ezeio products so I could try it out. Insofar as it is a standard Ethernet (802.3) product, I had no doubt it would work perfectly with AyrMesh, and, of course, it did – I just connected it to an AyrMesh Receiver with an Ethernet cable and it appeared on my network.

They were kind enough to send me one of the ezeio products so I could try it out. Insofar as it is a standard Ethernet (802.3) product, I had no doubt it would work perfectly with AyrMesh, and, of course, it did – I just connected it to an AyrMesh Receiver with an Ethernet cable and it appeared on my network.

What is cool about the ezeio is that it is a complete package – hardware, firmware, and back-end software – completely integrated and ready to plug in and go. It includes connection points for up to 4 analog inputs (configurable for 0-10V, 4-20mA current loop, S0-pulse, or simple on/off), Modbus devices, Microlan (1-wire) devices, and up to two relay outputs (up to 2 amps). This makes it a very versatile unit for both detecting and controlling things on the farm.

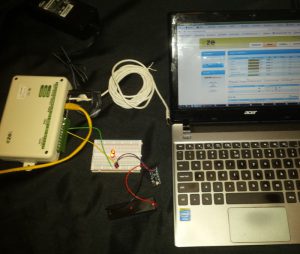

I set mine up on a table to see how it worked. The good folks at eze System included a Microlan temperature probe, so I set up my unit with that connected to the Microlan connector and a couple of LEDs (with a battery) connected to one of the relay outputs.

I set mine up on a table to see how it worked. The good folks at eze System included a Microlan temperature probe, so I set up my unit with that connected to the Microlan connector and a couple of LEDs (with a battery) connected to one of the relay outputs.

I then went to their web-based dashboard and started setting things up. It’s pretty simple – you get a login on the dashboard, and you add your ezeio controller. You can then set up the inputs (in my case, the temperature probe) and outputs (the relay) and then set up rules to watch the inputs and take appropriate actions. If you want to see the details, I have put together a slide show for the curious so I don’t have to put it all here.

I then went to their web-based dashboard and started setting things up. It’s pretty simple – you get a login on the dashboard, and you add your ezeio controller. You can then set up the inputs (in my case, the temperature probe) and outputs (the relay) and then set up rules to watch the inputs and take appropriate actions. If you want to see the details, I have put together a slide show for the curious so I don’t have to put it all here.

The bottom line is that I was able to quickly and easily set up a system that checked the temperature continuously and, when the temperature dropped below a certain level, lit up an LED. Big deal, I hear you say, BUT – it could easily have been starting a wind machine or an irrigation pump or some other machine, and it could have been triggered by a tank level switch or a soil moisture sensor or some other sensor or set of sensors. It also enables me to control those devices manually over the Internet, using a web browser, without having to “port forward” on my router.

The ezeio is a very powerful yet easy-to-use device which, in conjunction with the web service behind it, enables you to very easily set up monitoring and automation on your farm. For the do-it-yourselfer, it is a great way to get started on employing the Internet of Things (IoT) on your farm. Even if you’re not inclined to take this on yourself, any decent networking technician can easily set up your AyrMesh network and the ezeio to help around the farm.