We do occasional questionnaires and surveys to determine what our users want to do with their outdoor WiFi systems, and “security” and “cameras” have consistently been at the top of the list. So every few months I buy some new cameras and test them out here in the lab. I want to share with you my notes on the cameras we have sitting around here and what we’re still looking at. Spoiler alert: we haven’t found the perfect camera for farm/ranch security use yet.

We do occasional questionnaires and surveys to determine what our users want to do with their outdoor WiFi systems, and “security” and “cameras” have consistently been at the top of the list. So every few months I buy some new cameras and test them out here in the lab. I want to share with you my notes on the cameras we have sitting around here and what we’re still looking at. Spoiler alert: we haven’t found the perfect camera for farm/ranch security use yet.

The first category is “traditional IP cameras” – these are cameras that are pretty much self-contained and have more or less standard interfaces. They are “stand alone” devices that come up on your network and work. They are (mostly) very easy to integrate into an existing security system or home automation system, because they use standards like ONVIF and RTSP. These all require constant power, usually via a “wall wart” power supply, although some use Power over Ethernet (PoE).

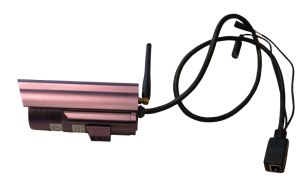

Cheap Ebay Camera

Foscam cameras – these are simple, older IP cameras with VGA (640×480) resolution and WiFi. There were also many clones that were similar and used the same firmware, available cheap on Ebay. They aren’t available any more, as far as I know, and they’re quite outdated, the picture quality is not good, but they were very simple to use. You might still find some clones on Ebay, but I wouldn’t bother given the choices that area available now.

Ubiquiti Cameras and NVR, courtesy of Ubiquiti Networks

Ubiquiti AirCams – I used to have a couple of these, but I have never found a way to use them effectively. Ubiquiti created a whole “system” with an NVR and cameras, but it was (in my opinion) good but never great. Their cameras didn’t do WiFi (all wired), and I lost interest in them. Apparently Ubiquiti did, too, as they seem to have discontinued the entire product line. There are still a lot of them available online, and they are a good choice for a building with Ethernet infrastructure.

Axis indoor camera

Axis M1030 and M1031 cameras – Axis products are generally considered the “best” IP cameras available, but the low-cost “M” series are the only ones that are WiFi-capable. The models I have are old and have been replaced by updated versions, which are undoubtedly even better. These are my “workhorse” cameras that keep an eye on things inside our lab buildings, but they can’t be used outdoors at all. Axis makes a very broad variety of cameras, but none of the outdoor cameras use WiFi, so they have to be used with an AyrMesh Receiver. They are relatively expensive, but very, very good.

Amcrest Camera

Amcrest cameras – Amcrest came out a few years ago with some remarkably high-quality, outdoor, WiFi-capable cameras. We have had one at our back door for a couple of years now, and it has been absolutely flawless and has a very nice picture. They are comparable to the low-end Axis cameras at a much lower price; in addition, they are outdoor and WiFi-ready. They use ONVIF and standard RTSP, so they are relatively easy to integrate into an existing NVR and/or security system. These are generally my “go-to” cameras – I recommend them quite a lot. The only shortcomings are that they are “traditional” IP cameras, requiring constant external power, so they’re not easily deployed away from a power source. However, they are my absolute favorite “traditional” IP camera for use where there is a source of power. You can easily buy them on Amazon.

Vivotek IB8369A camera

Vivotek – I have a nice outdoor Vivotek IB8369A camera. It’s a very nice camera, and Vivotek has a very large line of very high-quality cameras. I was interested because it was one of the first cameras I had seen that had more advanced “object detection” capability – much more accurate than the algorithm in most cameras at detecting people and animals moving into the scene. And it works well, but they do not make any WiFi-capable cameras. So the Vivotek has remained connecte to our network, but I don’t generally recommend them, especially now that advanced object detection is becoming available on other cameras.

The second category is “App-centric Cameras” – cameras that depend on an app to provide the “brains” of the camera.

Dropcam

The first of these was the “Dropcam,” which was acquired by Nest and Google. I was an “early adopter” of the Dropcam, later to become the Nest camera, and I found it to be very handy. However, it did not integrate into any home security system (until Nest introduced their own), they did not introduce an outdoor camera for years after the first, indoor camera, and the only way it can be used to detect motion and provide alerts is by paying a monthly fee to Google. Ring (now part of Amazon) came out with similar cameras, with similar shortcomings.

Wyze Camera

I bought a Wyze camera soon after they came out because I was intrigued by their price point: $20 for a good, simple, indoor camera, or $30 for one with pan-and-tilt capability. And I have been delighted with them: they can do motion detection and alterting, and you can easily access them through the very good Wyze app. They use a micro-SD card to store video on the camera, so you don’t have to have a subscription. They are currently my “go-to” for simple indoor cameras (e.g. folks who just want to see what’s going on in their house when they’re gone). They have introduced an outdoor camera, but it really belongs in the next category.

Sim-Cam

I also got a camera that touts itself as being much more capable in terms of locating motion: the SimCam Alloy 1S. This is a camera that uses a Passive InfraRed sensor to detect movement, and then uses advanced software techniques (which they call “artificial intelligence”) to identify people and other items in the camera’s view. So far, it has identfied me, the dog, and the cat next door as “person,” so I am not sure how well the person identification works. It’s a good little camera, and they have introduced a battery-operated indoor version. If they introduce a battery-operated outdoor version with a solar panel, I’ll certainly want to look at it.

The third category is “Battery-operated cameras” – these are app-centric cameras that can be installed remotely, without a power outlet. This is a very tricky category – there are a fair number of variations on this theme, but they are (so far) none that “look” like standard IP cameras. All are app-dependent, but most of them use local storage to avoid having to use “the cloud” to store video after a motion detection event. In order to minimize battery usage, they depend on a Passive InfraRed (PIR) sensor to detect movement, which then turns the camera on until the movement is done. You can get alerts through the camera’s app, and then access the video stored on the micro-SD card on the camera itself. However, none of these are currently capable of being integrated with a “traditional” security system, although some are able to integrate with popular home automation systems like Alexa and Google Assistant.

Reolink Argus

The first camera I used in this category was the Reolink Argus, which runs on four small “CR123” batteries. I was delighted with this camera for about 3 weeks (I had it mounted out where I was having some critter troubles, and it captured lovely video of a rat running around). I replaced the batteries, and, about 3 weeks later, it died. I then got some lithium 16340 batteries and a charger (the camera requires four). They lasted about 2 weeks between charges, and I was starting to get tired of changing the batteries when it had another problem: the latch holding the micro SD card broke, so it would no longer store video. It does not integrate with any “normal” security system, and it doesn’t have a way to integrate other power sources (e.g. a solar panel to keep the batteries charged), so it is currently sitting on a shelf.

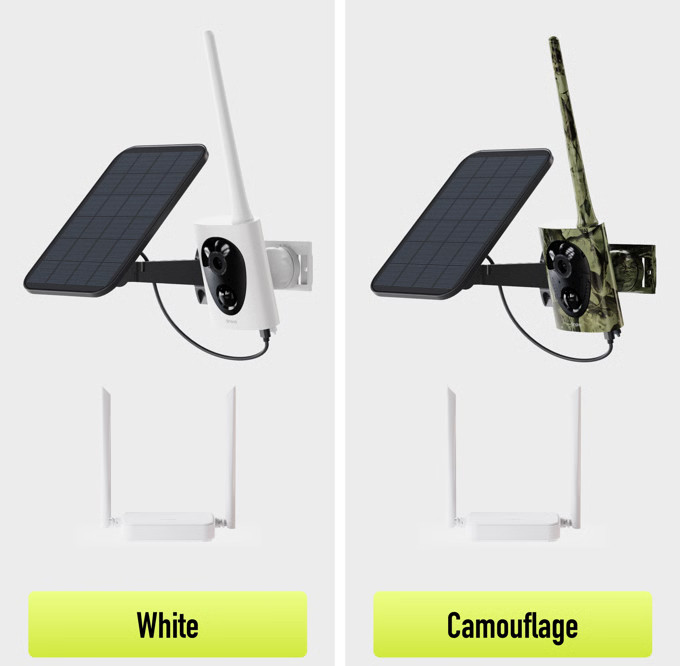

Mail-order camera

I then saw a relatively inexpensive solar-powered camera on Aliexpress.com and decided based on the specifications to give it a try. There were two immediate downsides: first, it shipped with incredibly bad batteries – they died and would not hold a charge after only 2 days. I replaced the batteries with known-good 18650 batteries and it has worked fine ever since. The second problem is that it depends on an app which is published by someone who is unknown (at least to me) and does not seem to be of the highest quality. That said, it has been working pretty reliably for a few months now.

Reolink Argus Eco

Reolink then released their Reolink Argus Eco, which, when paired with the optional solar panel, is functionally very similar to the camera above. I thought it would be interesting to compare and contrast with the “generic” camera above. It was a little more difficult to mount, since the camera and solar panel are separate, but worked essentially the same. The app comes from Reolink, which I found encouraging.

As noted, the performance of these two cameras is very similar. When they have a tight view of a somewhat secluded area (e.g. looking at a door from across the yard) they work very well – they alert every time someone walks through the scene with very few false alerts. When they are looking at a wider area with a lot of different things in the picture, they both generate a lot of false alerts. For instance, I have the Reolink in my brother’s front yard, looking at his cars in the driveway, and I get almost constant alerts from it when the wind is blowing, because it “sees” the branches of the trees moving. I had tested the inexpensive Chinese camera in his back yard and saw the same problem. I put the inexpensive Chinese camera in my back yard and pointed it at the back door, however, and it worked perfectly.

There’s not a single camera I can recommend without reservations. The Amcrest cameras are very good traditional IP cameras, and they integrate well with many traditional home security systems, but they require constant power and careful consideration around IP address planning (including router configuration) if you want to use them with an NVR or from outside your network.

The Wyze indoor cameras are so good and so inexpensive that they’re definitely my current choice for indoor cameras if you don’t need to integrate in with a traditional home security system. Their app is very good, and provides good alerts on motion, as well as good “on-demand” viewing. Unfortunately, they recently introduced an outdoor camera that, due to its design and the reviews I have read, I’m going to decline to test. They are going in a lot of directions right now, and not all of them will be successful, and I hope they “double back” and build a good, simple, outdoor solar-powered camera without the complications of the “Gateway module” and yet another wireless network.

Similarly, I like the Reolink Argus Eco for use in outdoor locations where there’s no power. Just turn off the motion detection and notifications if you need to use it in an area where there’s likely to be a lot of extra motion due to wind or other factors. There are a huge number and variety of similar cameras coming out of China – perhaps we can modify one or more of them to optimize it for rural use.

I’m going to keep looking and testing cameras here with an eye toward what works on the farm or ranch. Of course, I’m always eager to hear about what you have found, what you are using, and what you’re not using any more (successes and failures). Next up for me is the “EyeCube” – I’ll let you know how it goes.

We do occasional questionnaires and surveys to determine what our users want to do with their outdoor WiFi systems, and “security” and “cameras” have consistently been at the top of the list. So every few months I buy some new cameras and test them out here in the lab. I want to share with you my notes on the cameras we have sitting around here and what we’re still looking at. Spoiler alert: we haven’t found the perfect camera for farm/ranch security use yet.

We do occasional questionnaires and surveys to determine what our users want to do with their outdoor WiFi systems, and “security” and “cameras” have consistently been at the top of the list. So every few months I buy some new cameras and test them out here in the lab. I want to share with you my notes on the cameras we have sitting around here and what we’re still looking at. Spoiler alert: we haven’t found the perfect camera for farm/ranch security use yet.

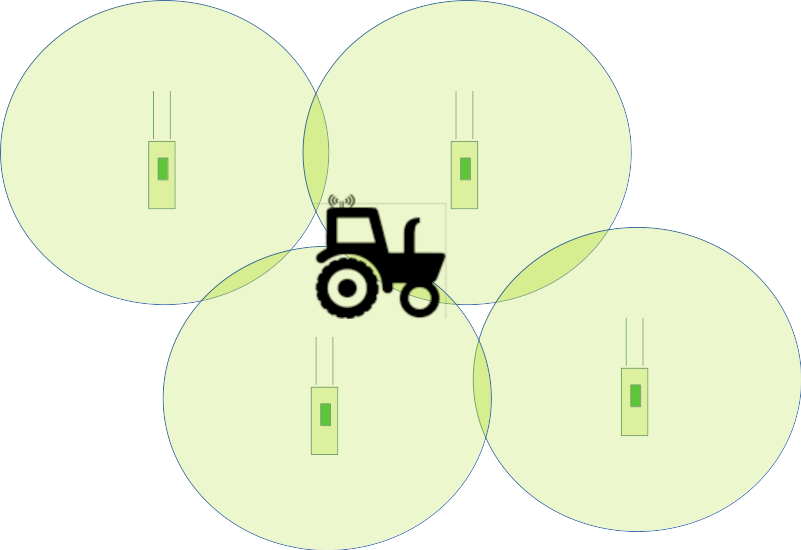

There is an image of farming – bucolic, peaceful, unfettered by the concerns of the technological age. It’s lovely, and many of us indulge it to some degree… but it is patently false. Agriculture is an industry moving quickly on the technology curve as markets demand more, higher-quality, and cheaper food and grains. Specialized implements, higher-horsepower machines, GPS steering, variable rate planting and spraying, and the cellphone have all had an impact on farm productivity. But that’s not all.

There is an image of farming – bucolic, peaceful, unfettered by the concerns of the technological age. It’s lovely, and many of us indulge it to some degree… but it is patently false. Agriculture is an industry moving quickly on the technology curve as markets demand more, higher-quality, and cheaper food and grains. Specialized implements, higher-horsepower machines, GPS steering, variable rate planting and spraying, and the cellphone have all had an impact on farm productivity. But that’s not all.

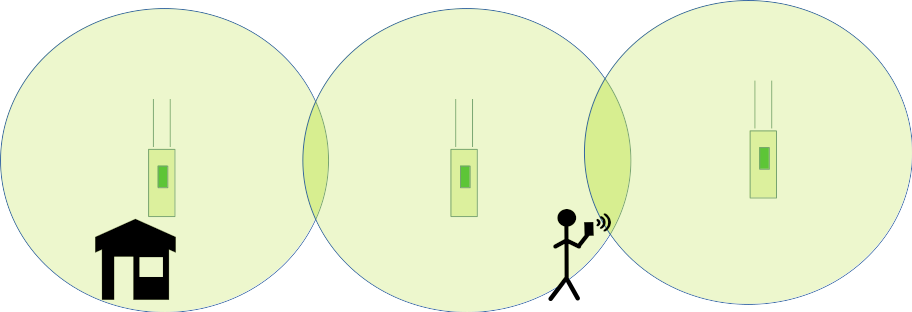

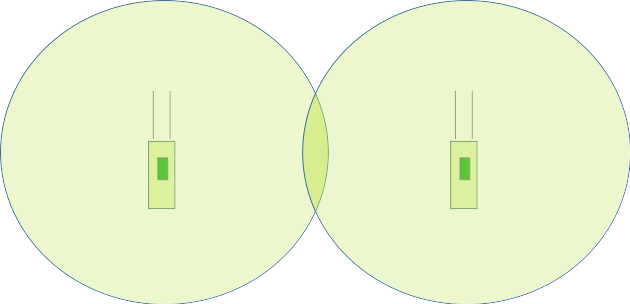

The new AyrMesh Hub2x2

The new AyrMesh Hub2x2

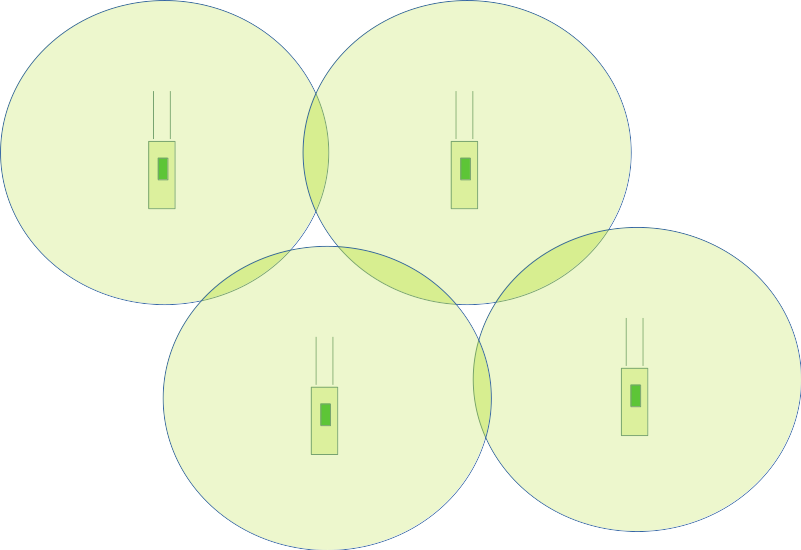

We are pleased to introduce the new model of the

We are pleased to introduce the new model of the  The ability to mount the Receiver on a flat surface (without additional hardware) is a feature that many users requested over the years, and the ability to add an outdoor PoE device will, we think, enable our customers to enhance security and operational awareness.

The ability to mount the Receiver on a flat surface (without additional hardware) is a feature that many users requested over the years, and the ability to add an outdoor PoE device will, we think, enable our customers to enhance security and operational awareness.