Courtesy of Davis Instruments

Much has been written about the use of remote sensors in farming, with soil sensors leading the way. I think it’s worthwhile to understand how these sensors work and what options are available

We have highlighted some of these products (gThrive, Farmx, Edyn), and there are others coming up including Cropx and AgSmarts that we have not been able to evaluate in depth yet, although they are very promising and appear to be more focused on “mainstream” agriculture rather than specialty crops.

The soil sensor people understand that, to have soil sensors near the plants, you have to have sensors that are battery-powered (because you don’t get enough sun under the canopy to use solar). Because of that, most soil sensors use a low-power radio system; many use a “Personal-Area Network,” usually based on the 802.15.4 low-power, low-bandwidth meshing standard. These networks allow the sensors to use very little power so the batteries can last for months or even years. Additionally, the bandwidth (the amount of radio spectrum they use) is so low that they can transmit a very long distance with minimal power – frequently hundreds of yards – and the meshing capability means they can cover a very large area in a couple of hops. So these sensor networks actually ARE practical for gathering data from sensors, even in a very large field.

gThrive sensors and gLink gateway – Courtesy of gThrive

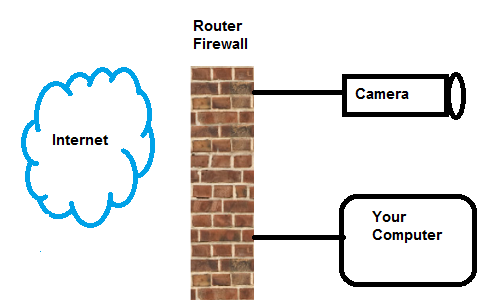

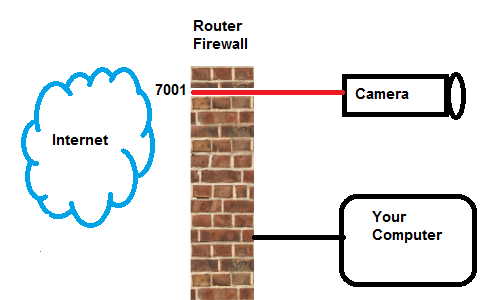

However, these systems, just like your home WiFi network, require a “gateway” device out in the field to connect them to the larger network (your AyrMesh network or the Internet). The Edyn sensor is an exception, because it connects directly to your WiFi network, but it is primarily aimed at gardeners, not commercial agriculture. Davis Instruments uses the weather station as the Gateway device, which makes it simple, but it does not use a meshing system, which limits how many sensors you can deploy. For almost all systems, sensors are not directly on your network or the Internet – the field network is a special network that only “talks” to the gateway device, and the gateway device “talks” to a normal Internet Protocol network – and that is usually a cellular modem connected to the Internet.

I generally discount analyst firms, but I have to reluctantly give kudos to Lux Research for hitting the nail right on the head: sensors are too expensive. With the exception of the Edyn, which you can buy at Home Depot (and connect to your AyrMesh network or other WiFi source), you have to buy:

- However many individual sensors you want,

- A Gateway device for your sensor network (possibly multiple gateway devices if you want sensors in multiple fields), and

- Cellular subscriptions for each gateway device.

This is a lot of “commitment” before you even figure out how to effectively use the sensors and the data that comes from them – thousands of dollars just to get started plus a monthly or annual commitment to get the data. These systems are being marketed primarily to folks growing wine grapes in California or vegetables in Arizona – high-value crops with severe water costs and restrictions.

There are changes coming, of course, but there are also ways to get started now with less commitment.

First, if you’re growing a few acres of cut flowers, organic vegetables, or other high-value, high-intensity crops, the Edyn system may be very useful. Put an AyrMesh Hub near your field and deploy the Edyn sensors and valves controllers. You don’t have to save a lot of time and water to justify the expense.

First, if you’re growing a few acres of cut flowers, organic vegetables, or other high-value, high-intensity crops, the Edyn system may be very useful. Put an AyrMesh Hub near your field and deploy the Edyn sensors and valves controllers. You don’t have to save a lot of time and water to justify the expense.

Davis Weather Envoy, courtesy of Davis Instruments

Second, Davis Instruments has a nice system that they don’t advertise much. Their Wireless Weather Envoy datalogger can be connected to any Ethernet network (e.g. a Remote AyrMesh Hub, an AyrMesh Receiver, or an AyrMesh Bridge) using their Weatherlink IP module. It can then connect to their Soil Sensor Station, which has up to four soil moisture and soil temperature probes. It will also connect to a Vantage Vue wireless weather station, which is a very high-quality, low-cost, integrated weather instrument cluster that you can put up in any field in a matter of minutes. There’s a small annual fee for their cloud-based Weatherlink service, but it makes the system VERY easy to use.

If you need more soil sensors, they also build an Envoy 8x, which has the ability to simultaneously “talk” to up to 8 stations – weather stations or soil stations – within about 1000 yards.

Either the Wireless Weather Envoy or the Envoy 8x can be tucked into the cabinet of the Tycon remote power system we recommend for field Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, and powered from the auxiliary power output on that system.

Either the Wireless Weather Envoy or the Envoy 8x can be tucked into the cabinet of the Tycon remote power system we recommend for field Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, and powered from the auxiliary power output on that system.

Third, if you do want to deploy many soil sensors using a system like gThrive or Farmx, you can connect the gateways in each field to an AyrMesh devvice to avoid exorbitant cellular fees for each gateway device. Their gateway devices have Ethernet ports, so they can be connected directly to an AyrMesh Remote Hub, Receiver, or Bridge unit, and you can skip the cellular bills.

We’ll have more on weather and soil sensors – if you have questions or comments, please leave them here (for public response) or contact us.

I read a LOT about the “Internet of Things” (abbreviated IoT) is in the news lately; you probably have see it too, and there is a lot of excitement around it. And I would argue there’s good reason for that – it is going to change everything, perhaps more fundamentally than cellphones and, later, smartphones. But it is important to understand what the IoT is, what it is not, and how it will affect life on the farm.

I read a LOT about the “Internet of Things” (abbreviated IoT) is in the news lately; you probably have see it too, and there is a lot of excitement around it. And I would argue there’s good reason for that – it is going to change everything, perhaps more fundamentally than cellphones and, later, smartphones. But it is important to understand what the IoT is, what it is not, and how it will affect life on the farm.

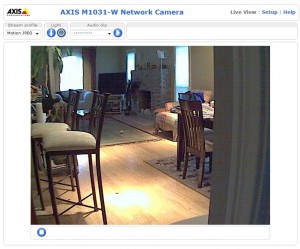

motion, and lots of other things) and robust built-in data communications infrastructure (WiFi)? What could you monitor? What could you control remotely (or even automatically), especially using the data you are getting from monitoring?

motion, and lots of other things) and robust built-in data communications infrastructure (WiFi)? What could you monitor? What could you control remotely (or even automatically), especially using the data you are getting from monitoring?

This is another example of the kind of technology that is available at very low cost when you outfit your farm with an AyrMesh network – each field can be outfitted with a FarmMap gateway device to communicate with their soil sensors, and you can connect the gateways to AyrMesh components (Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, depending on your network) to connect them to your network.

This is another example of the kind of technology that is available at very low cost when you outfit your farm with an AyrMesh network – each field can be outfitted with a FarmMap gateway device to communicate with their soil sensors, and you can connect the gateways to AyrMesh components (Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, depending on your network) to connect them to your network.