One of the hottest topics in “Ag Tech” at the moment is Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs, also known as drones) and the role they can play for the farmer. Drones are hot right now, in Ag and other industries, because technology has made them much more adaptable and much lower in cost.

One of the hottest topics in “Ag Tech” at the moment is Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs, also known as drones) and the role they can play for the farmer. Drones are hot right now, in Ag and other industries, because technology has made them much more adaptable and much lower in cost.

The possible benefits are tantalizing: an automatic, self-flying platform that can loft things into the air, take them where you need them, and take actions you prescribe. Just a few of the things drones can conceivably do for you:

- Take visible-light, near-infrared, and infrared photographs of all your fields at much higher resolution and in less time than satellite

- Get instant thermocline and other weather data (pop up 1000′ and check the temperature, wind speed, barometric pressure, etc.)

- “Run and get it” service for small items (see the beer drone and Amazon Prime Air)

When I was at the World Ag Expo a few weeks ago, there were several companies showing off drones and talking about drone-based ag services. Please make note of the distinction between drones and drone-based services, because, at the moment, it’s important. Or maybe not. I’ll explain as well as possible.

The Federal Aviation Administration has had a long-standing rule against the use of UAVs for “commercial purposes” – anything involving making money. Now, you can buy model airplanes with very sophisticated self-flying and video systems for fun or research, but not for any money-making purpose. However, a number of people couldn’t help themselves in making use of these amazing machines to enhance their businesses, and they have been getting “cease and desist” letters from the FAA. One guy named Raphael Pirker actually was fined by the FAA, giving him the opportunity to challenge the fine. He appealed to the National Transit Safety Board, and the administrative judge there ruled that the FAA did not have in place any actual regulations for the use of UAVs in non-navigable airspace, and therefore could not enforce the fine against Pirker. There’s a good article about this in Scientific American.

So, apparently, one currently can use UAVs for commercial pursuits, with some (not entirely clear) limitations. I’ll bet if you take your drone anywhere near a commercial airfield, for instance, you’ll get to meet some members of law enforcement and spend time with them. I’ll bet if you take your drone near any government installation, you will get to spend a serious amount of time with members of law enforcement and/or the military. In either case I’ll wager you’ll get to contribute a good amount of money to the government. And there are undoubtedly some private citizens who will happily shotgun your UAV out of the sky on sight.

I’ll also wager that the FAA (or some other part of the government) will create some rules about UAVs to protect people from stuff falling out of the sky on top of people and property, and having our neighbors peeking in 2nd (or 102nd)-story windows. But, for the moment, it looks like the skies are open, particularly out in the rural areas, and I expect farmers to be the first to benefit from UAVs. Some people like Chad Colby are already talking publicly about the opportunities.

Honestly, I think the current “state of the art” is mostly a plaything: the drones that are currently available are mostly manually radio-controlled and focused on live picture-taking. UAVs I have seen that might be put to use on the farm must be charged, taken to the field, flown around the field, and then the pictures (or other data) downloaded off the UAV (by bluetooth, WiFi, or transfer from some kind of flash card). This is a significant commitment of time, which limits how often you can really use the drone. A crop scout may be able to save a lot of the time he would normally spend by using a UAV to survey fields, but there’s benefit to the grower having a drone or drones that would continually survey fields.

The reason I am particularly interested in Ag Drones is because I believe they can become an important part of the day-to-day information-gathering apparatus. To be truly useful, however, I believe they must be:

- Autonomous: flying over your fields automatically without intervention. Ideally, they would have a “home” out in the field where they would stay, and they would do their flying at specific times with no human interaction needed.

- Smart: able to recognize problems and take appropriate action – recognize if there is something different in the fields, avoid danger, and report back

- Connected: automatically uploading data collected and sending alerts to you as needed. For instance, a drone flying over your fields taking infrared photos might use the wireless farm network to automatically upload the pictures to a service that automatically scans them for anomalies indicating crop stress.

- Self-maintaining: self-charging and self-monitoring, needing little maintenance and letting you know when it needs “help”

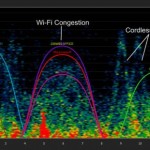

My own vision is that an Ag drone should be programmed with pre-configured flight paths and connected via WiFi with a wireless farm network for constant (or at least mostly constant) communication. It should be able to download changes to its schedule and pre-configured flight paths off the network, and It should also be able to land on a platform that will automatically charge the drone’s batteries for the next flight. Set up this way:

- The grower, scout, or agronomist doesn’t have to go out and mess around with the drone – it can just do its thing as often as it needs to (pending charging of the batteries)

- The data can be automatically collected on the grower’s PC or on a central server (on the farm or on the Internet) – it can even be automatically processed and problems (plant stress, aberrant weather conditions, etc.) can be automatically reported to the grower

- The drone works for the farmer, not the other way around.

All the pieces exist today to create drones that can meet these criteria, but I’m not aware of any pre-built planes or copters that are ready-to-use. However, there are open-source software projects that have built auto-pilot systems for drones and other robots (e.g. the ArduCopter), and there is discussion of induction charging of quadcopters in the “DIY” forums. And heavier-lift copters (capable of picking up fairly heavy items and transporting them) are also in the works. Imagine being able to get out your cellphone and “tell” your copter to bring you the parts you forgot back at the workshop, then hearing it whirring its way toward you a few minutes later. And then, when it delivers them, it DOESN’T TELL YOU YOU’RE AN IDIOT for forgetting the parts. For me, that would be nearly priceless.

In short, I think there are a lot of possible benefits from using UAVs on the farm, and I’m eager to see them start to deliver those benefits. However, I think a lot of the benefits are greatly enhanced by having the UAVs connected to a wireless farm network – I believe the two technologies will work hand-in-hand, each enhancing the value of the other.