There is a lot of talk about these technologies – every time I turn around it seems like I’m reading about or hearing an analyst who is saying that these technologies will revolutionize farming with “Internet of Things” devices. And they are exciting.

There is a lot of talk about these technologies – every time I turn around it seems like I’m reading about or hearing an analyst who is saying that these technologies will revolutionize farming with “Internet of Things” devices. And they are exciting.

The attraction for carriers to these technologies is that they can be added easily to an existing cellular (or other wireless) network, using existing backhaul, billing, and other infrastructure. Some of the technologies, like LTE-NB and Cat M1 (which Verizon and AT&T are reportedly testing) just require changes to the LTE station firmware (supposedly).

The appeal of all cellular technologies for solution providers, of course, is that they are easy to install – as long as there is a signal, they just put in an appropriate client radio and a SIM card, and the device starts sending data to a server.

The problem, of course, is that rural cellular networks don’t offer any data services to large parts of the rural U.S. today, and there are areas without even voice service. So there’s a significant investment needed on their part to make these technologies usable across rural America.

But that’s the problem: if you’re the company investing in deploying these technologies, you want to put them where the greatest concentration of potential users are, and that’s in cities. Every power meter, gas meter, water meter, parking meter, flow meter, streetlight, traffic sensor, etc. will be able to connect to the network – there are literally hundreds or thousands of potential connectors per acre in the city, vs. one to ten per acre in the country (except, perhaps, Napa). So, if I’m a shareholder for a cellular company, I do NOT want to hear they are building out rural infrastructure for LoRA or something else – I want them to concentrate in the cities, where those networks are most profitable.

Now, rural WISPs, telephone co-ops, etc. may choose to piggy-back one or more of these technologies on their networks to server local customers. Which WISPs? Which co-ops? Which technology? Your guess is as good as mine, although it is worth mentioning that Senet is a company that’s rolling out LoRA in a few rural areas, for instance. However, their coverage map makes it clear they are concentrating on cities, towns, and some farming areas in Missouri, Arkansas, and California.

Note also that, where there is connectivity, the carriers will want to charge a monthly fee for each device – that’s OK if you have a few devices, but, eventually, believe it or not, you will want to have hundreds of devices on your farm. I am already hearing from growers in specialty crops who have monthly cellular bills of over $1000.

Bottom line: I don’t see these technologies providing any real help to the majority of U.S. growers for the next 5 years, if ever. They will show up in some places as a local option, but it doesn’t pencil out on a national scale.

What does make sense is to put some sort of high-bandwidth wireless network on the farm/ranch (e.g. WiFi of some sort, like AyrMesh) and then, as needed, use WiFi-enabled sensors or run local 802.15.4 networks (e.g. Zigbee, 6LowPAN, Threads, etc.) in the fields for sensor connectivity. The sensors are cheaper, the networks are controlled by the growers, so they cover what needs to be covered, and, since it’s all on the farmer’s LAN, the data can easily be directed to a local server and needn’t leave the farm.

What does make sense is to put some sort of high-bandwidth wireless network on the farm/ranch (e.g. WiFi of some sort, like AyrMesh) and then, as needed, use WiFi-enabled sensors or run local 802.15.4 networks (e.g. Zigbee, 6LowPAN, Threads, etc.) in the fields for sensor connectivity. The sensors are cheaper, the networks are controlled by the growers, so they cover what needs to be covered, and, since it’s all on the farmer’s LAN, the data can easily be directed to a local server and needn’t leave the farm.

(Note: I’m not actually crazy about ZigBee, but it’s the best and cheapest we have available right now. I’m hoping for better in the future: something like Google’s Threads, but at 900 MHz.)

More to come on this subject…

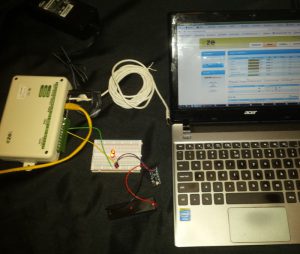

I set mine up on a table to see how it worked. The good folks at eze System included a Microlan temperature probe, so I set up my unit with that connected to the Microlan connector and a couple of LEDs (with a battery) connected to one of the relay outputs.

I set mine up on a table to see how it worked. The good folks at eze System included a Microlan temperature probe, so I set up my unit with that connected to the Microlan connector and a couple of LEDs (with a battery) connected to one of the relay outputs. I then went to their web-based dashboard and started setting things up. It’s pretty simple – you get a login on the dashboard, and you add your ezeio controller. You can then set up the inputs (in my case, the temperature probe) and outputs (the relay) and then set up rules to watch the inputs and take appropriate actions. If you want to see the details, I have put together a

I then went to their web-based dashboard and started setting things up. It’s pretty simple – you get a login on the dashboard, and you add your ezeio controller. You can then set up the inputs (in my case, the temperature probe) and outputs (the relay) and then set up rules to watch the inputs and take appropriate actions. If you want to see the details, I have put together a

First, if you’re growing a few acres of cut flowers, organic vegetables, or other high-value, high-intensity crops, the

First, if you’re growing a few acres of cut flowers, organic vegetables, or other high-value, high-intensity crops, the

This is another example of the kind of technology that is available at very low cost when you outfit your farm with an AyrMesh network – each field can be outfitted with a FarmMap gateway device to communicate with their soil sensors, and you can connect the gateways to AyrMesh components (Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, depending on your network) to connect them to your network.

This is another example of the kind of technology that is available at very low cost when you outfit your farm with an AyrMesh network – each field can be outfitted with a FarmMap gateway device to communicate with their soil sensors, and you can connect the gateways to AyrMesh components (Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, depending on your network) to connect them to your network.