Since we started marketing the AyrMesh system five years ago, we have gotten inquiries from folks who have large houses, offices, and small hotels/motels – can AyrMesh work indoors? The answer, of course, is that it can work, but it’s not optimal for a number of reasons, and we do not recommend it. AyrMesh is designed for outdoor use, mainly in rural areas.

Since we started marketing the AyrMesh system five years ago, we have gotten inquiries from folks who have large houses, offices, and small hotels/motels – can AyrMesh work indoors? The answer, of course, is that it can work, but it’s not optimal for a number of reasons, and we do not recommend it. AyrMesh is designed for outdoor use, mainly in rural areas.

We have been able to recommend the fine Open-Mesh products for indoor and urban outdoor use, but some new products have recently entered the market.

Eero was the first in this space, with a very nice-looking product and very good technical specifications. Unlike Open-Mesh, they do not have any way to mount their units outdoors, and they only offer one model (available in a 1-, 2-, or 3-pack).

Then, this week, Google announced the new Google WiFi product, utilizing a very similar approach of very nice-looking indoor meshing access points for larger houses. The Google WiFi products will be available in November, but they can be pre-ordered.

Open-Mesh uses their Cloudtrax website and apps to control their access points; we have used Open-Mesh here in the Ayrstone lab for years and found it to be excellent. It’s a fair bit more complicated than AyrMesh, but it has the more “commercial” features you might want for a business or a motel, and the more complex features are easily ignored for a home setup.

Open-Mesh uses their Cloudtrax website and apps to control their access points; we have used Open-Mesh here in the Ayrstone lab for years and found it to be excellent. It’s a fair bit more complicated than AyrMesh, but it has the more “commercial” features you might want for a business or a motel, and the more complex features are easily ignored for a home setup.

It’s worth mentioning that there have long been WiFi Repeaters (also known as “boosters” and “extenders”) that connect to your WiFi router and create a new WiFi signal, and devices like the Apple Airport routers that use “Wireless Distribution System” (WDS). Although a single repeater can work well, and three Apple Airport routers using WDS (one connected to the Internet and two “extenders”) can work, they don’t have the routing “smarts” of a real mesh network, and they can cause more problems than they solve. For a large house, a real WiFi meshing product like these will provide much better results without running Ethernet cables… of course, for the absolute best WiFi, there is no substitute for just running Ethernet and putting separate Access Points in each location you need WiFi. If you were clever enough to run Ethernet to the far reaches of your house before the drywall, all you have to do is plug in some dumb access points in the Ethernet – no need to mess with the indoor mesh.

The new Eero and Google WiFi products use apps to configure and control the network – I don’t know if there is a website option available, but I get the impression that the apps are the only way to control them. I don’t know about you, but my poor phone is “full” of apps, and I really don’t want another one.

So my own view is that these new players are not quite as good as what already exists in Open-Mesh, but, of course, your mileage may vary, Of course, they are being marketed like crazy, so you’re going to see them in the press all over the place.

What I think is important is that meshing WiFi is becoming mainstream, and, if you live in a large house, you don’t necessarily have to run Ethernet to get WiFi throughout the house.

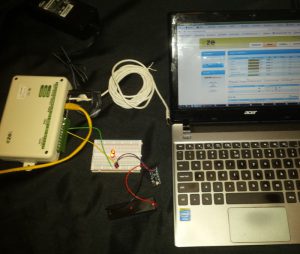

I set mine up on a table to see how it worked. The good folks at eze System included a Microlan temperature probe, so I set up my unit with that connected to the Microlan connector and a couple of LEDs (with a battery) connected to one of the relay outputs.

I set mine up on a table to see how it worked. The good folks at eze System included a Microlan temperature probe, so I set up my unit with that connected to the Microlan connector and a couple of LEDs (with a battery) connected to one of the relay outputs. I then went to their web-based dashboard and started setting things up. It’s pretty simple – you get a login on the dashboard, and you add your ezeio controller. You can then set up the inputs (in my case, the temperature probe) and outputs (the relay) and then set up rules to watch the inputs and take appropriate actions. If you want to see the details, I have put together a

I then went to their web-based dashboard and started setting things up. It’s pretty simple – you get a login on the dashboard, and you add your ezeio controller. You can then set up the inputs (in my case, the temperature probe) and outputs (the relay) and then set up rules to watch the inputs and take appropriate actions. If you want to see the details, I have put together a

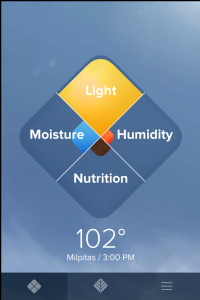

First, if you’re growing a few acres of cut flowers, organic vegetables, or other high-value, high-intensity crops, the

First, if you’re growing a few acres of cut flowers, organic vegetables, or other high-value, high-intensity crops, the

We wanted to quickly share an article published recently that impressed us quite a bit.

We wanted to quickly share an article published recently that impressed us quite a bit. I read a LOT about the “Internet of Things” (abbreviated IoT) is in the news lately; you probably have see it too, and there is a lot of excitement around it. And I would argue there’s good reason for that – it is going to change everything, perhaps more fundamentally than cellphones and, later, smartphones. But it is important to understand what the IoT is, what it is not, and how it will affect life on the farm.

I read a LOT about the “Internet of Things” (abbreviated IoT) is in the news lately; you probably have see it too, and there is a lot of excitement around it. And I would argue there’s good reason for that – it is going to change everything, perhaps more fundamentally than cellphones and, later, smartphones. But it is important to understand what the IoT is, what it is not, and how it will affect life on the farm.

motion, and lots of other things) and robust built-in data communications infrastructure (WiFi)? What could you monitor? What could you control remotely (or even automatically), especially using the data you are getting from monitoring?

motion, and lots of other things) and robust built-in data communications infrastructure (WiFi)? What could you monitor? What could you control remotely (or even automatically), especially using the data you are getting from monitoring? There are all kinds of new technologies and products available for farming – these new “AgTech” products hold real promise to change the practice and the economics of farming. But you have to evaluate them realistically to understand how they will help you improve your profit: increase revenue or save costs.

There are all kinds of new technologies and products available for farming – these new “AgTech” products hold real promise to change the practice and the economics of farming. But you have to evaluate them realistically to understand how they will help you improve your profit: increase revenue or save costs.

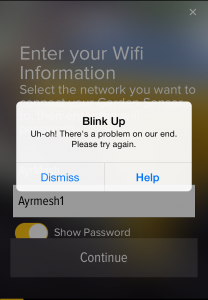

I should point out, of course, that none of these things deterred me in any way: I’m the crash test dummy for new devices like this, so I expect it to be rough when I first see it. My goal is to experience these rough spots so you don’t have to!

I should point out, of course, that none of these things deterred me in any way: I’m the crash test dummy for new devices like this, so I expect it to be rough when I first see it. My goal is to experience these rough spots so you don’t have to!

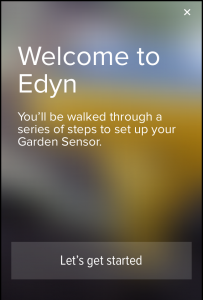

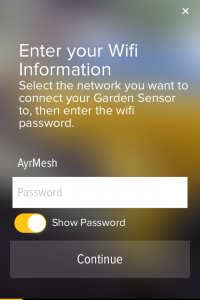

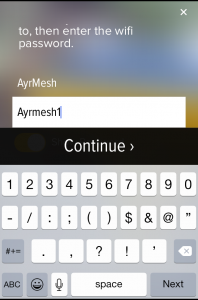

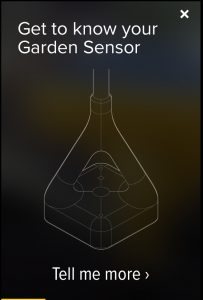

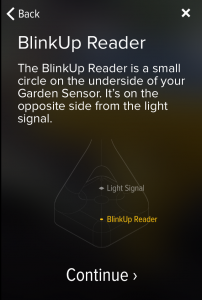

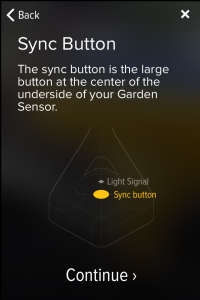

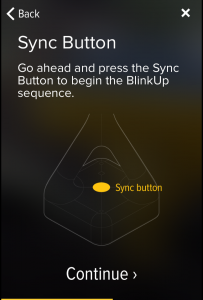

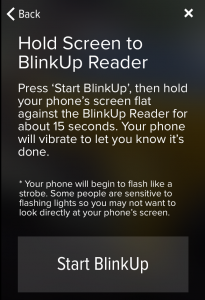

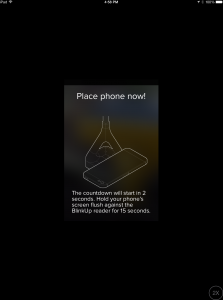

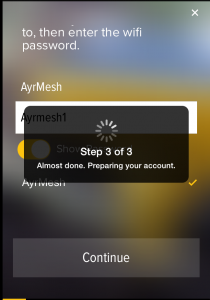

When I finally got the app installed on the iPad and got it started, I was taken through the process of creating an account and configuring the Edyn Garden Sensor. The Edyn is built with a VERY clever WiFi device called an “Electric Imp.” There is, obviously, no keyboard on the Sensor, so you have to get the WiFi configuration onto it somehow, and the Electric Imp uses a process called “Blinkup.” On the botton of the Sensor is a button and a small light sensor; you join the WiFi network (your AyrMesh WiFi network) on your phone or tablet, then type in the encryption passkey (from AyrMesh.com) in the Edyn app. You then hold the screen of the phone or tablet close to the bottom of the Sensor, and the screen blinks to send the WiFi credentials to the Sensor. The Sensor then joins the network, checks into Edyn’s servers (much like the AyrMesh devices do) and then appears in the Edyn app.

When I finally got the app installed on the iPad and got it started, I was taken through the process of creating an account and configuring the Edyn Garden Sensor. The Edyn is built with a VERY clever WiFi device called an “Electric Imp.” There is, obviously, no keyboard on the Sensor, so you have to get the WiFi configuration onto it somehow, and the Electric Imp uses a process called “Blinkup.” On the botton of the Sensor is a button and a small light sensor; you join the WiFi network (your AyrMesh WiFi network) on your phone or tablet, then type in the encryption passkey (from AyrMesh.com) in the Edyn app. You then hold the screen of the phone or tablet close to the bottom of the Sensor, and the screen blinks to send the WiFi credentials to the Sensor. The Sensor then joins the network, checks into Edyn’s servers (much like the AyrMesh devices do) and then appears in the Edyn app.

This is another example of the kind of technology that is available at very low cost when you outfit your farm with an AyrMesh network – each field can be outfitted with a FarmMap gateway device to communicate with their soil sensors, and you can connect the gateways to AyrMesh components (Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, depending on your network) to connect them to your network.

This is another example of the kind of technology that is available at very low cost when you outfit your farm with an AyrMesh network – each field can be outfitted with a FarmMap gateway device to communicate with their soil sensors, and you can connect the gateways to AyrMesh components (Hubs, Receivers, or Bridge radios, depending on your network) to connect them to your network.